BS 30480 – A different kind of Standard

N.B.: This post discusses suicide and mental health issues. Help is available if you need it, including from the Samaritans on 116 123. Links to other support resources are available via ABS, the Architects' Mental Wellbeing Forum and CIOB.

As Chartered Architectural Technologists, we love a good standard.

Well-developed standards help our profession to consistently deliver the high-quality, safe and comfortable homes and buildings our communities need, and I imagine many of us have a favourite PAS, Flex or BS that we fall back on. We've even elected a BSI employee as our Vice-President Technical.

So, it should come as little surprise that CIAT is applauding the launch of BS 30480 – it is hardly the first time the Institute has promoted new standards after all.

But BS 30480 isn't like other standards. It's not laying out processes for fire risk assessment or providing guidance on sound insulation. Instead, it is the very first standard developed globally to provide guidance and advisory recommendations for organisations to address suicide in the workplace.

The aims of BS 30480 Suicide and the Workplace – to give its full title – are two-fold. First, to enable organisations to identify, manage and (hopefully) mitigate suicide risks in the workplace, and second, to enable to organisations to properly support those effected by suicide.

These are ambitious goals, which require action at all levels of organisations. As such, the standard is wide-ranging, covering such topics as common myths and misconceptions about suicide, organisational culture and supportive workplace communities, risk factors, communication, confidentiality, crisis intervention and support after bereavement.

But why should this matter for Chartered Architectural Technologists in particular?

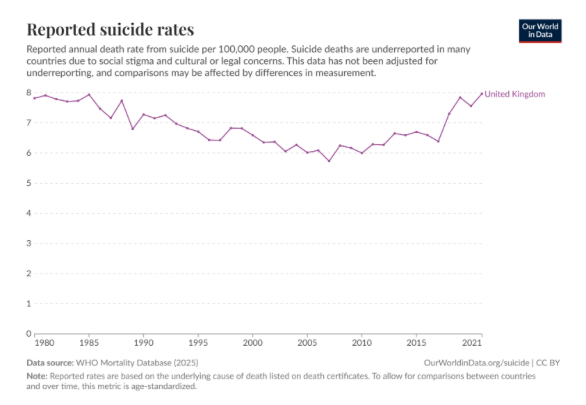

In the first instance, there is the human cost. Over 7,000 people died by suicide in 2023 in the UK and suicide rates have generally been on the increase since 2007. These human costs are felt particularly profoundly in our built environment sector.

Across the UK, the leading cause of death for men under 50 is suicide. Men under 50 also make up a large part of the sector's workforce. So, it should come as no surprise that across England and Wales there were more deaths due to suicide in the Skilled construction and building trades sector than in any other sector in every year from 2011 to 2019. There are likely to be many reasons for this, from underlying workforce demographics, to the physically demanding nature of the roles and the insecure nature of much work in the sector. But none of that excuses us from our professional responsibility to create supportive environments for the teams we work with, and to look out for those friends and colleagues who may be at risk.

Importantly, it is not only manual professions which are at risk of suicide. While ONS data from England and Wales shows only a single suicide among Chartered Architectural Technologists from 2011 to 2019, that is likely to be a reflection of the relatively small size of our profession – sadly, nearly 200 of our colleagues in architecture, surveying, planning, project management and associated technical and related roles died by suicide in the same time period. As team and project leaders, mentors and educators, and as friends and colleagues, we must recognise that we are on the front line of efforts to tackle suicide.

And there is another element to our professional responsibility.

Although suicidal ideation can be a symptom of both chronic and acute mental health issues, acting on such ideation is often impulsive, and limiting access to means of suicide is an important pillar of suicide prevention. In the UK, hanging and strangulation account for around half of suicides, while jumping/multiple injuries account for another 13%. That means that small design choices, such as removing potential ligature points, or physically restricting access to high-risk areas, can have an outsized impact on reducing suicide risk.

Of course, as with all design decisions, there are trade-offs. We must consider the context and use of a building and balance these risks. But weighing up different design considerations is something Chartered Architectural Technologists do every day (perhaps drawing on PAS 6462:2022 Design for the mind. Neurodiversity and the built environment). It is entirely right that we take this responsibility seriously, and keep in mind our professional purpose, which is to create spaces which enable people and communities to live well.

Our responsibility is clear. The only remaining question is how that translates into action.

As a starting point, I would encourage each and every one of you to read BS 30480, which is freely available on the BSI website. What you do next will depend on your own context.

For a sole trader, it might mean learning to recognise warning signs, and reaching out to your peers when you feel it is necessary.

For leaders in larger practices, it might mean reviewing existing policies or using BS 30480 as a template for a new suicide prevention and support policy, proportionate to the scale of your business. Or perhaps you would like to enable colleagues to find support discretely, in which case CIOB's Need to Talk Sticker will be worth exploring.

And if you don't have a leadership position, you can still play a part in fostering an open, supportive culture, and encouraging those you work with to do the same.

Ultimately, BS 30480 is a starting point. As with any standard, it's how we use it that will make all the difference.